Since September, I have been cleaning up a lot of stuff at home. Boxes of papers, including copies of literatures related to my old research and my children’s school notebooks, have gone to recycling.

Yesterday I found boxes full of old lab notes and data from early ‘90s. I was a brand new Ph.D in genetics and working as a postdoc at Yale University, struggling to figure out the mechanism of flowering using the model plant called Arabidopsis thaliana. This was my first independent research project.

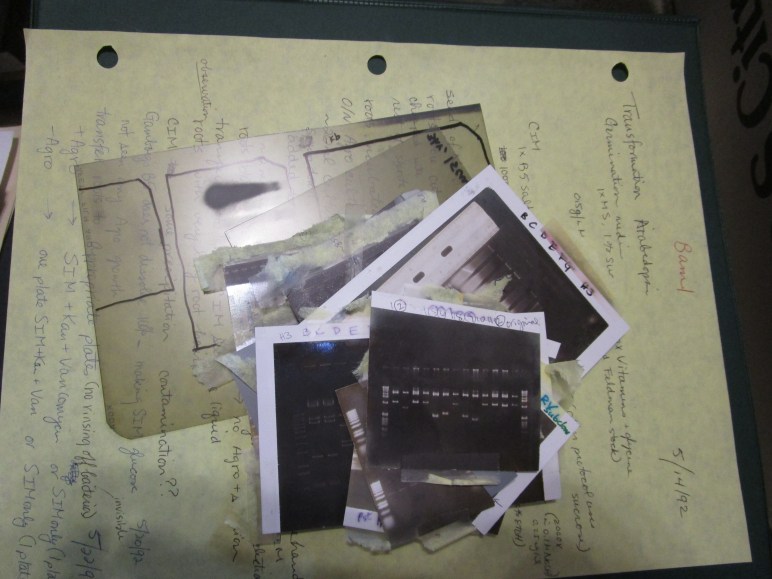

The first notebook was from near the end of the postdoc job and filled with jargons like BamHI, Northern, λH3, transformation and electroporation with Polaroid photos of gels, X-ray films and other stuff. Those are the language I used to use all the time. Without reading the contents I mindlessly went through the pages, ripping out photos and other objects so that I could recycle the paper. It felt as though all my feelings and interests went numb.

Then I opened a new binder. The first page was from December 1989 when I started the job while being nine months pregnant and a single parent with two little kids. It was a hard time.

It was indeed a ridiculous decision in many ways, but the hardest thing for me at that time was my research. I had a passion and what I thought was good strategies but the project was not getting anywhere. Until then, I had never really had to persevere in hard times in life. Whenever there had been a challenging subject in school, for example, I had written it off as uninteresting or unimportant to avoid the hard truth.

The only thing I could think of then was years of piano lessons in which I had to spend hours everyday for a few months preparing for a piece of music that might be only 10 minutes long. As much as I had hated those practices the memory of seemingly unrewarding work and the sense of accomplishment at the end gave me courage to stay on the research project. I gave myself one whole year before giving it up. It was a very long year.

Remembering this to be a difficult time, I started reading my entries while going through the pages. Funny, I could not make sense of much of them because I had only recorded dates and protocols. There were no big pictures: research purpose; strategies and rationales; definitions of various names of stuff; results and discussions. I know that those things were very obvious to me at that time, but the details had been buried in my consciousness under the decades of stories.

I found a significant entry in mid-1991. A fragment of plant DNA sequence that I had discovered earlier turned out to be similar to an important enzyme known in the animal kingdom. I actually remember the relief and excitement. For the next several years I chased this lead at Yale and also back in North Carolina. Well, the research never resulted in a glorifying discovery or a magnificent career in academia.

I actually loved doing lab research. It was like playing in a toy land with mini-discoveries every day. Talking about strategies and results were like playing open-ended games or solving puzzles. I spent many hours there. I thought I could be a great scientist and make great discoveries while just having fun.

But I now remember the days of self-doubts and anxieties.

The hard part was something else: Am I discovering anything significant? Is my manuscript accepted for publication? Do I have funding? Am I ahead of my competitors? Am I getting a permanent job? Am I a good enough scientist?

At that time, being good enough to land an academic position in the field of my degree was essential for me to live in this country because, without such a job, no visa would have been granted to me. Because I did not want to go back to Japan where my husband was, this was a huge burden.

All those yeas, while thinking that I was just having fun and doing what I wanted to do, I was constantly comparing myself to some external standards of what a good Ph.D geneticist should look like, and what a successful immigrant should be able to do.

When my husband—who eventually came back—and I finally got permanent residency after years of immigration nightmares, I literally felt a huge weight being lifted from my shoulders. Then, to my surprise, I was ready to do something totally different.

It is easy for me to be swallowed up by my circumstances and forget who I am and who I want to be. I feel hard-wired to sense cues from my surroundings and respond accordingly to unwritten rules around me. While this is probably a universal human behavior and has many benefits, I can also see the toll it has taken on my own well-being and those of others around me.

As I put the pages of the notebook into a recycling box, I breathed deeply and said thank you in my heart to my children, husband, parents and friends who stuck with me through the difficult time.